Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are a key trend in education technology in recent years, challenging traditional models of education (Johnson et al., 2013). Â In this post, I will examine research on MOOCs and online learning for education for sustainable development (ESD), as well as review the types of MOOCs available through major platforms such as Coursera, EdX and Futurelearn. I move on to look at other online learning approaches in ESD, which have useful principles which could be adopted in MOOCs for ESD. I will then highlight some of the benefits and challenges facing more wide-scale implementation of MOOCs in ESD.

MOOCs for ESD: an overview

Many MOOCs for sustainable are available online – a survey by Zhan et al. (2015) identified more than 50 offered via 10 different platforms – mostly EdX and Coursera. Although EdX and Coursera are American platforms, they noted that both “American and European countries [and universities] outperformed other English speaking countries as early birds in sustainability education using MOOCs”. Interestingly, the most frequent provider of MOOCs for sustainable development is Delft University in the Netherlands; all others identified were either North American or Northern European. The researchers did note that they may have missed courses in other languages than English or Chinese due to their lack of fluency in the language to be able to search for and retrieve courses online.

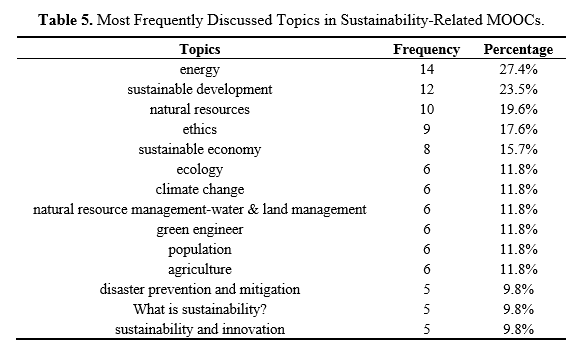

Zhan et al. (ibid) also surveyed the types of topics covered by the MOOCs for sustainable development. The topics identified are displayed in the table below.

Source: Zhan et al., 2015

From this one can conclude, that although many MOOCs covering the content of sustainable development exist, very few look at ESD per se targeting the specific pedagogies, strategies and approaches required for teaching and learning ESD.

Pedagogy and interaction in MOOCs for ESD

Zhan et al. (2015) identified the pedagogical models of MOOCs for sustainable development, finding that most adopt what they term “direct instruction […] without adopting specific pedagogies”, while 27% use project-based learning, 18% research-based learning and 10% team-based learning. Indeed, although “most MOOCs are well-packaged and well-organized, the instructional design quality is low” (Janssen, Claesson, & Lindqvist, 2015). One can infer from Zhan et al.’s paper that they understand direct instruction as a pedagogical approach which combines video lectures with “traditional pedagogical methods such as assignments, final examinations, reading lists, lecture slides, case study materials, field expert communication, presentations, poster activities, self-assessment and reflection.” In project-based learning, they state that “students are assigned to projects either individually or with a team, so that they can learn together when doing the project” while in research-based learning “[s]tudents pick a research topic and learn related subjects accordingly. The outcome of this pedagogy is usually research reports.” They define team-based learning in more detail:

“MOOC instructors divide students according to their individual interests, knowledge background, and location as reported in their initial online activities. Subsequently, each group selects a suitable task and accomplishes it through collaboration. The outcomes of the group work can be research reports or recorded videos through remote presentations to peer classmates, which helps to enhance social presence among learners.” Zhan et al.

MOOCs also provide some unique pedagogical means such as peer evaluation, social media, surveys, mapping locations, Google Video Chatting and offline get-togethers, in order to promote course quality in the massive open online environment. Peer evaluation opens up the opportunity for students to evaluate their classmates’ assignments. Surveys open up the opportunity for instructors to understand students’ levels and needs. Social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, etc.) provides an opportunity for learners to share knowledge and exchange ideas in their own social networks. Location mapping and offline get-togethers are both special features that are only suited to open education. The former activity shows students’ locations on the map and helps them to get acquainted with each other. The latter tries to gather students from the same place to meet with each other and build up deeper relationship (Zhan et al., 2015).

Principles from online learning for ESD that could be applied to MOOCs

Although Zhan et al.’s work demonstrates that many MOOCs use relatively traditional pedagogical models, and focus more on the sustainable development than ESD per se, an Australian case offers an interesting model that MOOCs might emulate. Foundations in Sustainability in Education (FSE), an online course for first year pre-service teachers offered at James Cook University (Tomas, Lasen, Field, & Skamp, 2015). The course leaders’ objective was both to tackle key sustainability topics, while also engaging “students in active, experiential and praxis-orientated learning”. The FSE course brought together an interdisciplinary team of academics with experience in science, social science, environmental science, online delivery and science education as well as an online designer. The approach combined more typical MOOC content like video lectures, reading lists, etc. with hands-on science experiments and real-world data collection to be reported back in the online course. To illustrate:

“Weekly tutorials provide opportunities for experiential learning and modelling of classroom pedagogies for science and sustainability education. […] students perform simple science experiments and activities involving the simulation of the greenhouse effect in a jar, the identification of soil samples and the use of dichotomous keys to classify plants and animals. All of the activities and experiments are designed such that they can be performed with simple everyday materials, making them accessible to online students”. Tomas et al.

They also engaged in place-based learning and investigations of local sustainability issues, and a formal written assessment designed to test both scientific and ESD pedagogical knowledge. Synchronous communication opportunities helped to create a feeling of belonging to a learning community and a more direct experience of interaction.

The JCU case appears to be unusual “interactive theories of learning do not seem to have permeated the research on online professional development courses for environmental educators” according to Li, Krasny, & Russ (2016).

Benefits and challenges of MOOCs for ESD

In this section I will consider the benefits and challenges of MOOCs for ESD, from three perspectives: pedagogical, technical and organizational

- Pedagogical

From a pedagogical perspective, the benefits of MOOCs are broadly similar in the ESD domain to other areas of education, in terms of enabling access to learning on a students own terms, facilitating collaboration, and enabling new forms of pedagogy spanning distances which are not achievable in traditional contexts.

“[I]n MOOC platforms, students can gain access to a video whenever they need it, and replay it over time” (Zhan et al., 2015). This illustrates how learners can revisit learning materials on demand via a MOOC to be able to enhance their understanding of key points – however, this does not apply to the social elements of MOOCs in the same way, as other students and course leaders are typically only active within the timeframe of the MOOC. On the other hand, this can be somewhat mitigated by the use of social media which enables facilitators and students to keep in touch beyond the course. Als “use of social media can increase course ‘stickiness’ and facilitate student interaction in ways not exploited by traditional courses” (Zhan et al., 2015). And even when using collaborative tools, “teamwork is more difficult than in face-to-face courses, because it requires additional organization and is sometimes not easy to control in a massive user context” (Zhan et al., 2015).

Social media and other collaborative tools will only have success if they include

“[c]arefully designed course objectives and success criteria [to] facilitate increased student engagement and participation. For instance, setting requirements on number and frequency of posts ensures deeper student interaction (Zhan et al., 2015). Otherwise the risk is that the MOOC simply clones a traditional pedagogical model which does not reinforce ESD principles of social problem solving, collaboration and restructuring of educational hierarchies.

Despite the potential for more innovative pedagogies, MOOCs still face challenges in implementing more innovative pedagogies. “Team-based learning, project-based learning, and presentations are pedagogical methods that have not been used sufficiently in the current status of MOOCs” (Zhan et al., 2015).

From an ESD perspective, MOOCs can also be challenging in that they drive the educational experience through an online platform. Some of the principles of ESD is to encourage real-world engagement, and experience of the natural environment. Using models such as the one described by Tomas et al. (2015) can help to mitigate this, but the pedagogical understanding among teaching staff of how to marry ESD content, pedagogies and technology is often lacking in many institutions (Tella & Adu, 2009). The organization and targeting of content to specifically acquire both ESD content as well as ESD skills is also a major challenge, “devising courses that don’t just teach about sustainability but teach for sustainability” (Tella & Adu, 2009).

2. Technical

Technical benefits and challenges for MOOCs, similarly to the pedagogical ones, are both general and ESD specific. At a general level, MOOCs have implications for costs, content ownership, learning curves for both students and instructors as well as access. From a more ESD-focused perspective, MOOCs present some technical barriers in terms of integration of ESD specific tools and pedagogies, driven in part due to the lack of expert HR in this area.

From a general perspective, use of MOOCs reduces technical costs for educational institutions to deploy online courses, as only relatively few public platforms are used by numerous universities such as EdX, FutureLearn and Coursera (Zhan et al., 2015). This significantly cuts the need for technical support, maintenance, hosting costs, etc. as resources are shared. On the other hand, this does bring risks as it raises questions of ownership of content, and long term sustainability of platforms – “ if a MOOC provider ceased to provide a service, what happens to the course content? This is somewhat mitigated by the move by EdX to make their platform open source, and thus reusable by any provider (Daniel, 2012). The relatively few technology platforms for MOOCs available in the market also brings pedagogical and organizational benefits: once students have learned how to use a platform, they can use it to take many courses; the same applies to course leaders in terms of creating and structuring content on the MOOC platform. Another challenge with MOOCs if that few MOOCs (with the exception of some examples highlighted by Commonwealth of Learning) are adapted for access by those in developing countries with low bandwidth or difficulty accessing digital platforms.

From an ESD perspective, current MOOC platforms do not offer specific functionalities to support ESD ICT-based pedagogies. For instance, “citizen science” tools to share and visualize data, mapping and geographic information systems, etc. (Wals, Brody, Dillon, & Stevenson, 2014) or immersive virtual laboratories (Wu, Longkai; Looi, Chee-Kit; Kim, Beaumie; Miao, 2013) are not well integrated with MOOC platforms. They can however point to external tools and embed simulations, which may require additional logins and passwords, which can act as a barrier to a seamless learning process. The pedagogical affordances of MOOC technical infrastructure remain relatively hierarchical and instructor-centred, as few have been built with an explicit focus on more innovative pedagogies and can be a barrier to optimal collaborative design (Laurillard, 2014a). Both of these former issues reflect the fact that relatively few people have a combination of both a technical background, pedagogical knowledge and ESD (Tella & Adu, 2009) which would enable and drive closer integration of these issues in the MOOC tools available on the market. Bringing together interdisciplinary teams could help to mitigate this.

3. Organisational

In organizational terms, MOOCs raise general issues such as completion rates, language availability and subtitling, training, costs and processes for production and deployment of MOOCs, and careful design of hands-on elements.

At a general level, a major challenge for all MOOCs is the very low completion rates (Wagner et al., 2005). Anecdotal evidence (via personal communication with European Schoolnet) does however indicate that educators are more likely to complete MOOCs than the average. The European Schoolnet Academy MOOCs (European Schoolnet, 2014) have completion rates closer to 50%. A MOOC jointly run by Institute of Education and UNESCO (Laurillard, 2014b) also showed higher than average completion rates among teachers: 1 in 9 teachers registered completed the course (Laurillard, 2014a).This illustrates that MOOCs targeting in-service teachers may be more likely to be completed than for the average MOOC participant.

Although MOOCs are available for free and online, the language barrier remains significant as the ESD materials are mostly in English, some in French and very few in regional languages (Tella & Adu, 2009). The use of subtitling helps, but is typically only in English rather than local languages (Zhan et al., 2015). Subtitling and human translation cannot help to facilitate collaborative interactions either. Integration of new dynamic translation tools like Skype Translator (Microsoft, 2016c) could be introduced by instructors to support collaboration, and automated translation tools for web content such as Google Translate (Google, 2016) and Bing Translator (Microsoft, 2016a) could be more effectively embedded in MOOC interfaces. As automated translation tools have significantly increased in quality in recent years, this relatively simple step could radically increase the reach of MOOCs – although they would still not address minority languages which are not available in translation tools. Increasing access would better address the ESD objective of integrating developing countries most at need of ESD.

Effective deployment of MOOCs requires training for MOOC educators, including on speaking and video lecturing, creating online materials, social media, and facilitating the online learning process (Janssen et al., 2015). Similarly, more training is required to bring together both ESD pedagogy and MOOC-based pedagogical approaches.

Finally, MOOCs can be relatively low cost to create and deploy – for example around $25,000 but can also be produced more expensively (up to $150,000) (Laurillard, 2014a). MOOC content can be revised and reused in consecutive courses, reducing the costs for further reuse of the content – although HR needed to moderate and animate the courses will still involve some investment. Course content would also require refreshing every so often, which can be an expensive process if full video production teams are used to create video. Using new tools like Office Mix (Microsoft, 2016b) can further cut costs however, by enabling instructors to create their own content without the need for a video crew or graphic designers. As the content is created slide by slide, it is also more easily adjusted than via traditional video editing.

Finally, including real world and sustainability focused activities also poses an organizational challenge. Participants are likely to be in radically different environments and countries, so activities must be designed extremely flexibility to enable participation despite these differences. Thinking globally and designing experiments which require very low investment in materials and equipment is critical to ensure they are open to all.

Conclusions

Despite the massive growth in MOOCs, sustainable development still remains a relatively new topic of coverage, and ESD more specifically is very rarely offered via MOOCs. Sustainable development MOOCs, although involving a relatively large number of people, are relatively traditional in terms of pedagogical model. They thus do not always respect the philosophical underpinning of ESD which requires more innovative social models of knowledge building as well as a combination of theoretical with real world investigation. A number of online learning approaches in ESD have good models for MOOC instructors to follow in improving the ESD aspect of MOOCs. MOOCs have huge potential benefits from a pedagogical, technical and organizational perspective, but also pose a number of challenges in addressing ESD effectively. One of the major obstacles to overcoming these challenges is the lack of staff in universities and technical companies who are able to bridge the gap between technology, ESD and pedagogy. Building multi-stakeholder teams to address this – as well as increasing access to ESD would be a major step forward to tackle this.

Bibliography

Daniel, J. (2012). Making Sense of MOOCs. Seoul, South Korea.

European Schoolnet. (2014). European Schoolnet Academy. Retrieved April 25, 2016, from http://www.eun.org/academy

Google. (2016). Google Translate. Retrieved from https://translate.google.com

Janssen, M., Claesson, A. N., & Lindqvist, M. (2015). Design and Early Development of MOOC on “Sustainability on Everyday Lifeâ€: Role of the Teachers. In The 7th International Conference on Engineering Education for Sustainable Devleopment (pp. 1–8). Vancouver, Canada.

Johnson, L., Adams Becker, S., Cummins, M., Estrada, V., Freeman, A., & Ludgate, H. (2013). NMC Horizon Report: 2013 K-12 Edition. Austin, Texas.

Laurillard, D. (2014a). Anatomy of a MOOC for Teacher CPD. London.

Laurillard, D. (2014b). ICT in Primary Education: Transforming children’s learning across the curriculum. Retrieved August 10, 2015, from https://class.coursera.org/ictinprimary-001

Li, Y., Krasny, M., & Russ, A. (2016). Interactive learning in an urban environmental education online course course, 4622(April). http://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2014.989961

Microsoft. (2016a). Bing Translator. Retrieved from http://www.bing.com/Translator

Microsoft. (2016b). Office Mix. Retrieved April 25, 2016, from https://mix.office.com/en-us/Home

Microsoft. (2016c). Skype Translator. Retrieved from https://www.skype.com/en/features/skype-translator/

Tella, A., & Adu, E. O. (2009). Information communication technology (ICT) and curriculum development: the challenges for education for sustainable development. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 2(3), 55–59. Retrieved from http://www.indjst.org/index.php/indjst/article/view/29416/25424

Tomas, L., Lasen, M., Field, E., & Skamp, K. (2015). Promoting Online Students ’ Engagement and Learning in Science and Sustainability Preservice Teacher Education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(11).

Wagner, D. a, Day, B., James, T., Kozma, R. B., Miller, J., & Unwin, T. (2005). Monitoring and Evaluation of ICT in Education Projects. Evaluation, 1–17. Retrieved from http://www.infodev.org/en/Publication.9.html

Wals, A. E. J., Brody, M., Dillon, J., & Stevenson, R. B. (2014). Convergence between science and environmental education. Science, 344(May), 583–584.

Wu, Longkai; Looi, Chee-Kit; Kim, Beaumie; Miao, C. (2013). Immersive Environments for Learning: Towards Holistic Curricula. In Reshaping Learning: Frontiers of Learning Technology in a Global Context (pp. 365–384). Berlin: Springer.

Zhan, Z., Fong, P. S. W., Mei, H., Chang, X., Liang, T., & Ma, Z. (2015). Sustainability Education in Massive Open Online Courses : Sustainability, 7, 2274–2300. http://doi.org/10.3390/su703227